Actor and musician David Soul, best known for his role as “Hutch” in the iconic 1970s television series, ‘Starsky and Hutch,’ is also a humanitarian and activist. Among his rights work, he was arrested in 1985 during a demonstration defending Rev. D. Douglas Roth, who was fired by the Lutheran Church for his anti-corporate sermons. Soul has also aided the rehabilitation of black bears on behalf of the World Society for the Protection of Animals and the Idaho Black Bear Rehabilitation Center. Additionally, he’s been a voice for children, minorities, and recently for dogs who suffer the extreme cruelties of the Asian dog meat trade.

Thank you, David, for taking the time to talk to us about animals.

You’re welcome. But I have a confession to make—something that’s haunted me all of these years now—and I’m 72. When I was six years old, before our family had gone to Germany, I was at my grandfather’s house and I found a little baby bird who was out of the nest and obviously scared and hopping around. [pauses] So I took little stones and threw it at this baby bird till I killed it. I didn’t think anything of it. I used it for target practice basically. But as the years have gone on, I’ve never forgotten that moment—an indelible memory of a six-year-old kid—of the pointlessness, of the stupidity, of a little boy who knew nothing about what he’d done, whose only thought was the self-gratification of being able to aim good. And it killed this little bird.

I never forgot that. It’s one of the few things I remember as a child, as a young child. It was 66 years ago, and it’s still an indelible mark on me. And today, I feel very … [pauses to search for a word] … sad … that I did that because I have a different perspective today. But I guess, in some of us, there’s a justification—whether it’s target practice or a clean kill—to kill or mistreat animals. [pauses] That’s my confession.

Did you have animals in your family at that time?

No, not at that time. As a child, much younger than six, we had a Doberman Pinscher who was my nursemaid. My parents would put me on a blanket outside, and then the Doberman Pinscher, the killer police dog, would just be there with me. He looked after me. I remember Fritzy—his name was Fritz—but I don’t remember a lot about him, except that he was always there and I could touch him and play with him and hang onto him. He was very patient—except when the mailman or the milkman or anybody came by, and then he wasn’t quite as friendly with them as he was with me. His aggressiveness got to the point where it was intolerable, so my parents decided they had to give him away.

They gave him away once and Fritzy came back—on his own. And they said, “Well, that means we need to put him a little further away next time.” So they gave him to a family 25 miles away—and I’ll be damned if that dog didn’t find his way home again. My parents finally gave him away someplace where he couldn’t run back, or where he was chained so he couldn’t go anywhere, having been warned that he would try to get home again. I really didn’t know what happened; my parents told me what happened. But I do remember Fritzy. I do remember the dog. And I’m just telling you the story my parents told me.

You learned the loyalty of a dog.

Absolutely. You know, you see it time-and-time again where the dog who always met his owner, his friend, at the train station, and then the guy dies, and the dog goes down to the train station and waits for The 505 every night. “He’s coming. He’s coming.” Or the one who sits by the graveside and doesn’t move. There’s such beautiful lessons to learn from these animals, from these dogs. They are much more sensitive to feelings than we often give them credit. They know what’s happening, they just don’t have a way of expressing it in verbal terms. And they probably don’t have a mind that gets in the way all the time. Our minds have a tendency to exploit situations and turn them into events that didn’t really happen. Dogs go with the truth … and that’s why I love them.

How many dogs have you had in your lifetime?

Let’s see … [searches his memory] There was Fritzy. And Fritzy 2. [laughs] He was a wire-haired dachshund. There was Claremont. [laughs more heartily] A hot dog. Big ears down to here. Close to the ground. What are they called? Basset hounds! “Claremont” suited him. [mocks a basset hound bark] “Roo! Roooo! Rooooooo!” It’s not really a bark, it’s just a “Roo! Roooo! Rooooooo!” … it’s not like … “Ruff! Ruff! Ruff!”… [laughing] He was just a charming little comedian.

Then, of course, I had Dublin.

Is Dublin the only retriever in the pictures we see?

I had more than one Labrador. But Dublin was my man. He was with me 24/7. I had complete respect for this dog. He could do everything, but he demanded respect. He just demanded it. Because he did everything. And it wasn’t, “Hey, look what I can do with my dog.”

It was amazing what he could do. “Hey, Dublin, go get the paper for me.” He’d paddle out of the house, go through the gate, pick up the paper, return with the Los Angeles Times in his mouth, come back, and drop it. “Get me a beer, will ya?” He’d open the refrigerator. [laughs] I taught him how to do that. He’d open the refrigerator. I put the beers on the bottom shelf, and he’d grab a beer in his soft mouth, which he had, and then bring it back. I could give him a hand signal just to indicate to him [pushes hand down, very subtly], that much, and he’d lie down. “We’ll be in the room for a while, Dub.” And he would be quiet. But the minute I’d say, “Let’s go, Dub,” he’d jump up, “Oh, yes, let’s go! Right! Okay!”—and he’d be right there. [laughs fondly]

He fed off your energy.

He was such a special, wonderful animal, and gentle and kind. I mean, what a lesson. That, for me, is what animals are all about.

You see that in him where he’s lying under the piano in your television series, The Yellow Rose, at your feet, content just being with you.

That’s the way it was. Unfortunately, there was a divorce in the X family and she took the boys, unbeknownst to me, up to Idaho, around the corner, right? Anyway, the kids loved Dublin, and so it was right that he stayed with them.

You did what was best for him.

I did what was best for him, I suppose, but best for the boys, because they adored him, and their having him… well, he was kind of my surrogate. He sort of looked after what I couldn’t. That’s exactly what he was and what he did. So, when I came up to visit, he was over the moon.

When he passed away, he didn’t pass away where anyone could see him. He knew he was going. He was 12, I think. And he wandered off the property and laid down by a juniper tree, and died. He didn’t want to lay it on anybody. I’m convinced of it. I’m convinced that’s why he didn’t stay at the house. You know, I think the purpose of dogs, and I’ve said this many times before, that dogs, that animals are a gift, and the way we treat and regard them is the way we regard our fellow man.

Is that something you learned from your family, your father?

No. [pauses] No, no, no. It didn’t have anything to do with him. No. In a word.

You learned it from animals themselves?

I learned it in my own interpretation. It’s my own idea. It’s not my dad’s. My parents weren’t into animals the way I am.

Did you have horses? I see you can ride.

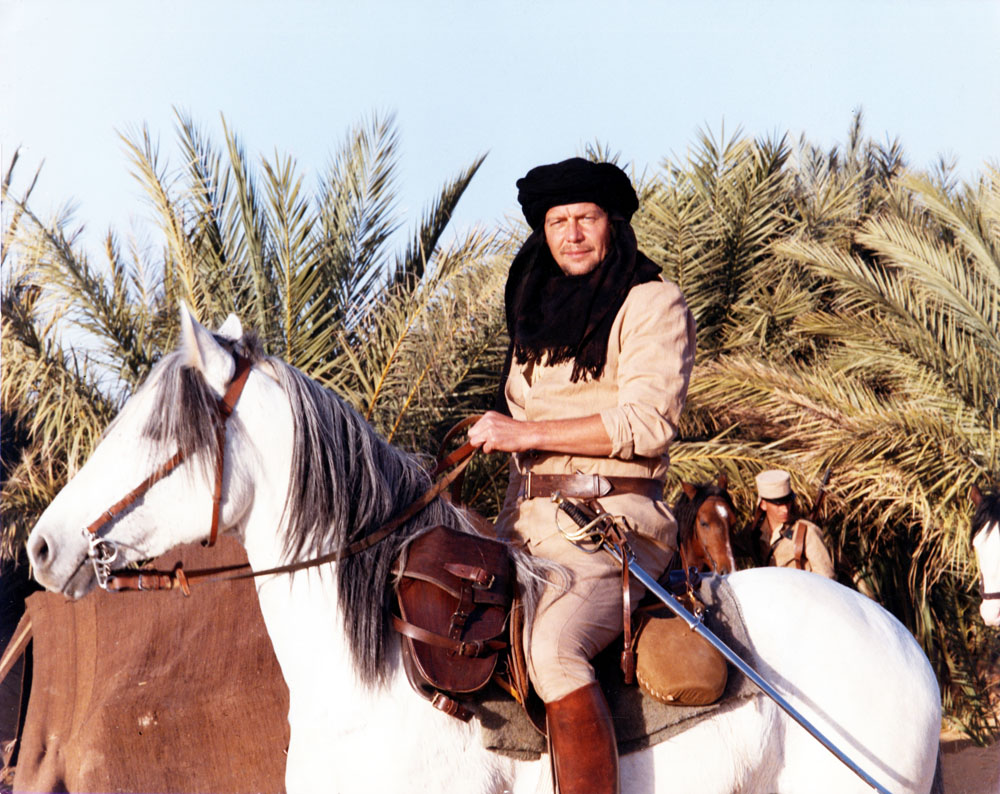

I’ve ridden all my life, since I was a teenager, certainly. My first professional job in North Dakota was in a musical play called ‘Teddy Roosevelt Rides Again,’ and it was held in the Theodore Roosevelt National Park. There was a theater there and I was part of this group of actors who worked for the Shafers, of the Gold Seal Floor Wax Company, and I worked there punching cows, moving them around, and then we’d go work at night as part of this show—with my guitar, singing, [breaks into song] “Oh Shenandoah, I long to see you, Away you rolling river…” You know, that one… so I did that, and, of course, I’ve done a lot of films riding both Western and English saddle.

Did you ever have a relationship with a particular horse?

Yes, I did. Atlas. The one I had in Morocco while working on the film, The Secret of the Sahara. I worked on that film for what, two months? [thinks, then confirms himself] Yeah, two months. We had 200 horses on the shoot. At the end of the shoot, the wrangler … the ramrod… the gaffer for the horses … we became friends … and he said at the end of the shoot, he said, “You wanna go with me across the Atlas mountains?” I said, “absolutely,” so I took a couple extra weeks and traveled with him on Atlas across the Atlas Mountains in Morocco.

We’d come into Berber villages, all mud huts, everything was mud, and the first place you go is to the well in the middle of the town square. Then you’d look at some doorway, and the people inside would motion you over, and you’d go in. They’d seen you coming for miles, and they’d have shish kabob already in the oven, and they had the bread ready, and the tea, and the water for your hands, everything. Desert people are always like that because there’s an Islamic tenet, particularly in the Sahara, that you take care of even your worst enemy for three days. You feed him and you house him and you make sure he’s taken care of for three days—and then you can kill him. [laughs, then more seriously adds] …because they know the desert will take everyone, therefore they are kind to strangers.

So you were with the same horse for a while.

Atlas was a wonderful Arabian. Fast. Sure-footed. I loved him. He was white. “Hi Ho Silver, away!” [laughing]

Do you have any memories of camels? I hear they’re ornery creatures. Is that anything you experienced?

Actually, I had quite an experience, but not because the camel was ornery. I’ve never had that experience with a camel and I’ve ridden a number of camels in film without incident. One particular camel was wonderful. I really liked him. Like Atlas, the horse I rode in Morocco, we got along beautifully.

So, I did this film and they brought in a veterinarian from Cairo because the script called for the camel to ‘expire’ in the southern Sahara. The vet gave him a shot, a tranquilizer shot, but nobody had spoken to the camel about this. The camel wouldn’t go down. They shot him again. He wouldn’t go down. By noon, we had 12,000 feet of film trying to get this big, 1300-pound white camel down.

I’m working with him in front of a camera set up about 600 meters away with a long lens. I’m coming down this sand dune leading the camel with my left hand and all of a sudden I get this strange feeling that something is happening behind me. I turn just in time to see the camel lurching toward me, stumbling, so I threw up my right arm to protect myself, and the camel grabbed my arm in his mouth. As soon as he righted himself, he let go of me, and I rolled down the hill, bleeding like a sonofabitch, profusely. But the camel still refused to go down. This proud animal was not going to go down their way, not even with tranquilizers. He was a man of the desert.

Eventually, I was whisked off to a doctor for stitches, and they dragged the camel back to the top of the hill, to this mound at the top of the hill, and finally put him down. He succumbed with his head and his neck facing downhill. A camel has the same digestive system as a cow, so what happened was … the camel actually died of asphyxiation.

When I got back from the doctor, thinking the camel was okay, I found out that they finally got the shot of the camel expiring. A real one. He was dead. They lopped off his head and sent it to Cairo for rabies. The next day, this silver jet appeared in the sky, this corporate jet, and two guys with briefcases from Lloyds of London flew in, along with a bottle of Scotch, to chase me around the hotel to get me to take 21 rabies shots. The Scotch was to soften me up. So, every day, for 21 days in a row, with a needle about that long [shows a length between his fingers of eight inches] I took these shots into my stomach till there was no place left on my tummy where they could stick a needle. It’s one of the worst things that’s ever happened to me. And what was supposed to take two weeks, but it took six, the results came in that the camel was clean.

That’s just part of the story. That’s what happened to the camel and to me. But production didn’t think about what happened to the guy who supplied the camel. In the desert, the camel is one’s wealth, and this one was a great white, beautiful animal. His owner lived in a little village, so nobody paid attention to this guy. My son Kristofer was there standing in for me and he almost killed this veterinarian who’d killed the camel. He was livid, absolutely livid. And I was in no condition to do anything. The agents from Lloyds of London left, and the vet left, but no one took care of the guy whose camel they’d just killed. So I got a pickup truck and I went out to this little village and I grabbed him and put him in the front seat. We drove down to Nefta to the camel auction where—with all my per diem—I bought him a baby white camel. We put the camel in the back of the truck and drove back to his village—and he was over the moon. What they didn’t do for him, I did for him. I was appalled that they hadn’t done anything for him. He’d become a non-entity.

As had the camel.

I agree. The way they treated the camel was also appalling. It was sinful what they did to that animal. I mean, I understand what happened, but it should have been a very simple thing. I helped tranquilize bears in Idaho to reintroduce them into the wild, and they went to sleep for a while and came back to life again.

Doing that to the bears was in the bears’ best interest.

Absolutely. So they had to take extra care to treat the camel properly. It wasn’t in his best interest. He didn’t agree to it. He never got in on the conversation. They took advantage of him. And when it didn’t work the first time, they just kept shooting this poor animal with more and more tranquilizer till it killed him. I questioned why they kept doing that, but then I got bit, and the story turned in a different direction. It became about the possibility of my having rabies.

How did you go from dogs, horses, and camels into bears?

Easy. [laughs] There was no transition there. I was contacted by Sally Maughan of the Idaho Black Bear Rehabilitation Center to lend my voice to help the bears. The appeal from her was a genuine one and I was going to be in Idaho anyway, so I said sure. She blew me away by what she was doing. I went out there with a camera crew from a television show, so they came along to film a lot of what I did there.

What was your role?

We drugged the bears and tagged them, which is the normal procedure. There was all kinds of political bullshit going on at the same time because a lot of people didn’t support what Sally was doing. It was stupid. But this particular ranger really supported her and I helped him and his crew, drugging and tagging the bears. We put them in cages in the back of snowmobiles and drove up into the mountains. They’d already found some natural caves up there, so I carried a couple of the bear cubs to the caves.

[laughs] My very first job in television was in Flipper. I played a junior ranger in the Everglades and the main thrust of my role was to save a bear cub from quicksand. I hurried along a branch and dropped into the quicksand to save this bear—who nearly killed me. They’re tough, tough little motherfuckers. [laughs] And I remembered that experience in Flipper while I was at Sally’s place. While I was playing with the bear cubs… well, they didn’t take prisoners. I remember it clearly. It was fun—once they were drugged. [laughs]

Anyway, I carried a couple of these babies and stuck them into the holes, pushed them into the caves, knowing—because I was told this—that, after they recovered from their drugged stupor, they’d find their way out of the caves, wander around, and figure out what had happened, and then go back into the caves to sleep it off.

Sally doesn’t get too close to the bears, so they won’t count on her for everything. She puts these bears into large cages, into as natural an environment as possible, so she isn’t their main source of experience in the world. She doesn’t want to be a mom to the bears. That isn’t her job. And the bears she rehabs are there because their mothers have been killed; they’ve been shot by hunters or run over by timber trucks—because they cut timber up there. Because of Sally’s reputation for saving bears, bears from all over—from Michigan, Wyoming, northern California, and Washington—are sent to her. But the idea is to strengthen them enough to give them a head-start to turn them back into the wild. I take my hat off to her. That’s her number one goal. She doesn’t want to become too close to the bears so they won’t depend on her or they’ll never make it in the wild.

Even with animals in places like Africa, in those areas, where you take a lion cub … he’s gotta have enough strength and enough savvy in his early years to be able to survive in the wild.

So, in the spring, the baby bears will wake up and be on their own. Then we check on them… from their tags… to make sure they’re gonna be all right.

It was quite an extraordinary experience. It really was, I must say.

Speaking of Flipper, Ric O’Barry, the dolphin trainer from the series, is now an activist against dolphin captivity after one of the dolphins died in his arms. He’s been arrested countless times for interfering in Japanese dolphin slaughters that provide dolphins to marine parks worldwide. Did you know Ric?

I didn’t know Ric. But I saw the footage from his Oscar-winning film, The Cove. It’s pretty gruesome. [extra long pause and shudder, then quietly continues] I didn’t have any scenes in Flipper with a dolphin, so I will have to defer. My connection was with a bear—and he mauled me.

He was playing for real.

Yeah, he didn’t know we were acting. I tried to tell him. Once we got into that fucking stupid pool filled with polyurethane, this bear panicked, and he took his panic out on me—with claws as long as my fingers.

Didn’t they expect that something like that might happen?

They were assured by the handler, “Oh, not a problem! He’s just a baby cub. They know how to handle themselves.” But, looking back, when you put an animal in a situation like that, he’s going to panic. It was my first television job, so what the hell did I know? [laughs]

That was reality TV before reality TV.

[sarcastically] Yes, Laura, that’s what it was. Thank you for making that comparison.

[laughing] I was trying to get something out of it.

[laughing] Okay. I will join a movement to destroy all cubs. [hearty laughter] Tough little varmints they are. You’ve gotta know your place when you go in to say hello because mommy isn’t there to protect you from themselves. No, but, seriously, I love the little bears. I really do.

Tell me how you learned about the Asian dog meat trade.

I saw footage on a local television network of dogs being rounded up and trucked to slaughter, so I contacted you to let you know that what I’d seen had made me literally sick and that we just had to do something.

It must have been all the more heartbreaking for you to see such horror, given your love for dogs.

I don’t think it comes from a love for dogs. It’s just the way animals get treated. And it isn’t just dogs. It’s the way pigs and cows and chickens, and all those other animals that we eat, get treated. There’s no respect for them. Animals are cheapened in order to make a profit. That’s bullshit. That’s what really pisses me off.

Eating dogs over here is illegal on one hand, but it’s also not part of tradition in this country. It is in the east, in Asia. So, it’s not that I’m gonna try to change their culture. That’s not my thing. My thing is to stop the way in which they treat the animals. That’s what I really resent, how they’re treated. That’s why I got pissed off. The minute I saw the video… and then the additional footage and pictures you sent me… I just couldn’t believe how these dogs were crated and shipped without water or without food—and for hundreds of miles. They’re just pieces of meat. It’s sickening.

Which is how all ‘livestock’ animals are treated; shipped hundreds of miles without food or water—even in the U.S. They just happen to not be dogs.

That’s what I’m saying. Pigs. Chickens. Cattle. They’re just there to satisfy greed and to make a profit.

Bill Maher was kind enough to post our dog meat campaign video, the one you made in conjunction with The Animals Voice, on his Facebook page, where it received more than 200,000 views. Some of the commenters called you a hypocrite for ‘saving dogs while beating women’—

I don’t beat women.

I know that. You know that. But how do you respond to these allegations and this persistent belief and characterization of you from an isolated incident that occurred more than four decades ago?

Well, you just said it. ‘An isolated incident that occurred more than four decades ago.’ I’ve grown a lot since then. Who hasn’t? But I feel no need to defend myself. People will say whatever they’ll say—and they’ve said a lot worse about President Obama. If he can handle it, so can I.

Animals are treated horrifically for food, all around the world, but they’re also abused for entertainment; for example, bullfighting.

That’s a complicated issue. I tend to go after things like the dancing bears in Turkey and some of the eastern countries, where they rip out their claws and pierce their noses with rings attached to chains, and make them ‘dance’ for tourists.

How is the cruelty of a bullfight different from dancing bears?

I’m not saying it’s different. I’m not arguing on behalf of bullfighting, believe me. It’s just that bullfighting has been around for centuries. How is anyone going to change something as entrenched in a culture as it is?

We’re actually making inroads to ending bullfighting. It’s dying around the world as younger people find interests in other things. Another way we’re killing it is by ending government subsidies that keep it alive, by putting it to the people in those countries and letting them decide whether it’s a barbaric practice or art.

That’s smart. That’s fantastic. “Which one do you want? Bullfighting or education?” It’s a smart way to approach it, to put it to the people. It’s a very wise thing to do, to follow the money. It’s an admirable campaign.

You’ve been waging your own admirable campaign: to restore Ernest Hemingway’s 1955 Chrysler convertible for the Hemingway Museum in Havana, Cuba. Does the bullfighting issue play into your Hemingway project?

It doesn’t, no. I wasn’t into Hemingway for his bullfighting. I love his writing. That’s what I love. There are a ton of things I don’t agree with with a lot of people, but it doesn’t mean I’m going to be strident against them. I’ve always loved Hemingway, his writing, and when I had a chance to go to Cuba as a British citizen, not realizing there’d be problems with my U.S. citizenry, but when I had a chance to go to Cuba, I grabbed it. The first place I went was to the Hemingway house, which is now a museum, where he lived for 22 years, before he came back and … committed suicide.

He’s my literary hero. His writing is simple. Not complicated. It’s very descriptive in its simplicity. He doesn’t exaggerate with a lot of flowery bullshit. He’s not self-conscious about it. He just tells a story and I like that.

I remember as a kid reading The Old Man and the Sea. That’s what turned my head around and made me want to go to Cuba. The interesting thing about the Old Man and the Sea, which I didn’t see at the time, but I can see it now, is that the old man is a fisherman and he’s got to do that in order to live. I go along with that, if that’s the way you live. I don’t have any problem with Native Americans and the way they live. Every single last piece of a bison they’d use for something—their clothing, their houses, their food, their needles, their arrowheads, everything. They respected the earth that gave them the buffalo. They respected the buffalo. They didn’t mistreat them. That was left to the white man to do.

So, this old man … he goes out into the sea and catches this big fish. He manages to bring it in … and then he turns around and he protects it when the sharks come to eat it. [in a disbelieving voice] The sharks attack it and tear it to pieces and all he comes back with is a skeleton! The image I have is of a guy protecting the fish that he’s killed.

There’s an allegory there. Respect. It’s respect.

There’s a central American tribe that holds an apology ceremony before it hunts and kills an animal, to let the animal spirit know how sorry they are to have to take its life, but also how grateful they are to have the sustenance it provides them. We don’t have that relationship with animals anymore.

Absolutely. You’re absolutely right. And what we think now is that meat comes from a butcher. Light comes from a switch. Water comes from a tap. That’s what we think. As long as it’s there, we have no regard from where it comes. And what happened to it before it got to us isn’t germane, isn’t important. It’s “gimme, gimme, and gimme now,” and that attitude has seeped its way into almost every aspect of our ‘organic’ life.

That’s one of the things your son, Jon, has fought against, the alienation of nature, and he’s interested in doing more to rekindle that relationship. Is that something you taught him?

No. No, I don’t think so. He discovered all of it on his own. He started out in Wisconsin, tracking the wolf because they had gotten rid of the wolf up there and the deer population skyrocketed, and they realized they needed the wolf to balance nature. That’s the wonderful thing about nature, isn’t it? Animals instinctively go to places like that because there’s a reason for it, you know? And just because the wolf is killing some of your sheep, you find a way to deal with that, because if the wolf isn’t there, the deer population is gonna grow in a way that cannot be sustained. So Jon went to track the wolf, to find out what their habits were, so they could reintroduce the wolf into the right places. He was working for the Audubon Society up there. This is something he started way back when, on his own.

Do you think people are only ever really going to get back to a relationship with animals if they have experience with animals and nature, or is it something that can be taught?

I don’t think we’re going to change anything with adults too much; once in a while we can. But I do think young people are hungry for this kind of thing. I really do. Jon has worked most of his educational life as a student and also as a teacher, introducing young people to these various themes, and these ideas, and he uses a very visceral type of approach. Look at the work he has done, starting with a drain on the street in Shreveport, Louisiana, following the waterways all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico, and he’s fulfilled this thing, cleaning out ponds full of washing machines and bicycles and tires and shit like that, and the place came back to life again. These kinds of things need to be celebrated, really celebrated. But you still have to go in and convince the city council that this is the way forward, and it’s like, “oh really? here comes another one of those do-gooders, the people who want to change the way we do things.” And it’s a piss-poor attitude and it’s taken on by so many people.

There’s so much human grief in the world, too, not just for animals and nature.

Particularly in areas like Africa, for different reasons in different places. Over here, it’s like we’ve forgotten about all that shit, until you’re hit with a drought like California has experienced, and agriculture has gotta figure out how it’s gonna make money. Otherwise, you don’t really pay attention. If we took some of that technology and put it to use on a wide scale in Africa to preserve land that is now parched and useless, people could actually be somewhat self-sufficient, particularly growing things, vegetables and grain, I mean.

I think there’s a connection between human and animal problems, but for different reasons. I don’t know. It’s a bigger question than this old pea brain can get its head around at the moment. I don’t really have the answers to anything. I just tell you how I feel.

Do you feel an obligation to use your celebrity status to shed light on charitable causes?

The answer is: No, not because of my celebrity status, but because I’m a human being, and in that sense, I have a right. Celebrity doesn’t have anything to do with it. These are things that, you know, you don’t … they’re not necessarily passed on to me. They’re things I discovered throughout the experiences of my life, and I discovered what’s important to me and what’s not. That’s not celebrity. That’s just David. A person. The fact that somebody else might listen, well, that might have something to do with celebrity, but that’s a different issue. It’s not like I take something on because I’m a celebrity. It’s not part of it. Do you understand what I mean?

I’m asked to do charity work by people who don’t have the same attitude that I just explained to you. I do these things because I’m a human being—that’s what comes first. But they approach it more from, “I have a project. I need a celebrity.” I’m sorry, but I don’t do it for those reasons. I really don’t.

What I want to tell them is: “I want you to understand something that’s not going to happen in this conversation, but down the road I want you to think about it. I’m not interested in this issue because I’m a celebrity. I’m interested in this issue because I’m a human being.”

The first thing I consider is, ‘Is this something I care enough about to put myself on the line?’ Generally speaking, it comes from me, if it’s something that’s genuine and real and I can actually identify with and get behind. I’m happy to do that. Once I’m behind it, I find every conceivable way of moving something forward based on my recognition, but not as a celebrity, not to begin with.

You’ve worked on behalf of humans and animals.

It’s all one thing.

It’s all for the betterment of the world, right?

It’s better for wherever it is we’re talking about it. I’m not going to change anything in the world at large. People themselves have got to change how they live. But where we see need, we address the need, and where we see problems, we address the problems. So, it’s not up to us, to me or anybody else, to fix things ‘out there.’ It’s up to people. I think what’s important here is just to be able to say, ‘Look, I don’t know all of the answers, guys, but I do know—and you can see it, if you’d just admit it—that there are problems out there. And don’t try to avoid it, because there are.’

We have real climate change problems and we have real problems addressing the needs of people for food. Things are only going to get worse as we add more people to the planet; it’s already trying to support seven billion people. How are you going to change seven billion people? Well, you change it where you live. Me. You.

And everyone reading this.

For more information about David’s ‘Cuban Soul’ project, please visit Cuban Soul. For more information about black bear rehab, please visit Idaho Black Bear Rehab. For more information about the dog and cat meat trade, please visit The Animals Voice.

Interview © 2016 by Laura Moretti for The Animals Voice